Deep Work

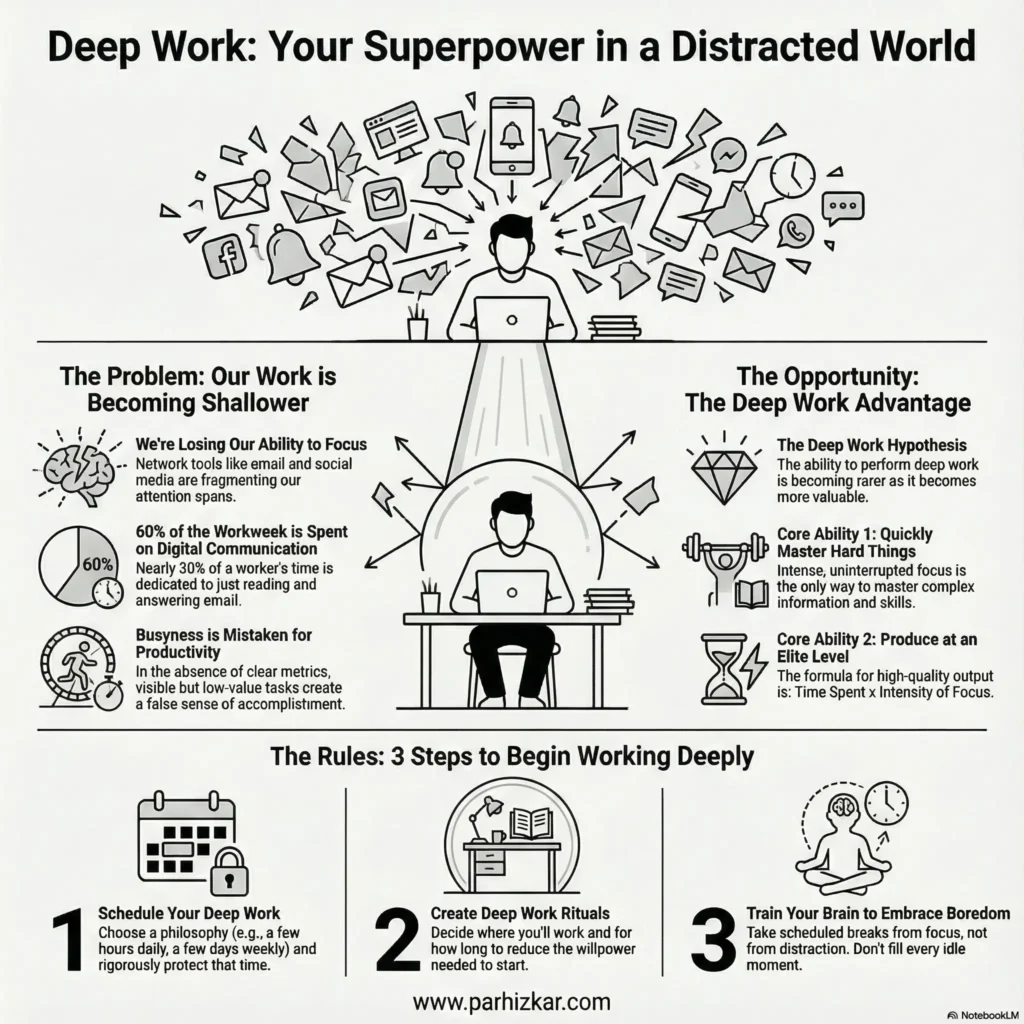

Do you ever feel trapped in a cycle of being constantly busy but never truly productive? Your day is a frantic blur of emails, meetings, and notifications, yet at the end of the week, you struggle to point to any meaningful accomplishment. If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. A 2012 McKinsey study found that the average knowledge worker spends over 60% of their week on electronic communication and internet searching. Given the explosion of collaborative tools since then, this figure has likely only increased.

The antidote to this modern malaise is a concept called Deep Work. As defined by researcher Cal Newport, it is:

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.

This stands in stark contrast to its opposite, Shallow Work:

Shallow Work: Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend not to create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

Our work culture is drowning in the shallow, leaving little room for the deep. This article reveals four counter-intuitive but powerful truths from Newport’s research that can help you reclaim your focus, escape the frenzy of the shallows, and thrive in a distracted world.

1. Deep Work Is the Superpower of the 21st Century

The central argument for prioritizing focus is what Newport calls the Deep Work Hypothesis:

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive.

This hypothesis is built on the reality of the “Great Restructuring” of our economy. As technology races ahead, it’s dividing the workforce into those who can work with complex machines and those who are replaced by them. To land on the winning side of this divide, you must master two core abilities—and both depend entirely on deep work.

The Ability to Master Hard Things Quickly

Our economy is built on complex, rapidly changing systems. To remain valuable, you must master the art of quickly learning complicated things. Consider the story of Jason Benn, a financial consultant who realized his job could be automated by a simple Excel macro. He decided to become a computer programmer, but first, he had to overcome his own digitally distracted habits. Benn locked himself in a room with only textbooks and notecards, training his ability to concentrate for hours at a time. After two months, he not only excelled in an elite coding bootcamp but also landed a job that more than doubled his salary.

Benn’s story is a microcosm of the new economy. As the source material notes, “Some of the computer languages Benn learned, for example, didn’t exist ten years ago and will likely be outdated ten years from now.” To master such hard things requires intense, uninterrupted concentration. If you can’t learn, you can’t thrive.

The Ability to Produce at an Elite Level

In a globally connected economy, being mediocre is no longer a viable option. To succeed, you must produce the absolute best stuff you’re capable of producing, a task that requires depth. Individuals who thrive, like data analyst Nate Silver or programmer David Heinemeier Hansson, do so because their deep work allows them to produce at an elite level that stands out in a crowded marketplace.

The rarity and value of this skill are what make it, in the words of business writer Eric Barker, “the superpower of the 21st century.”

2. Your Brain Is Wired for Busyness, Not for Productive Deep Work

It’s a frustrating paradox: just as deep work becomes more valuable, our work culture actively conspires against it. This isn’t an accident. It’s a direct consequence of what I call the “metric black hole.” In knowledge work, it is “objectively difficult to measure individual contributions to a firm’s output.” This ambiguity creates an environment where inefficient and distracting behaviors can take root and thrive. Two in particular stand out.

The first is the trap of Busyness as a Proxy for Productivity. This leads to a perverse and inefficient workplace culture where the appearance of work becomes more important than the actual value produced.

In the absence of clear indicators of what it means to be productive and valuable in their jobs, many knowledge workers turn back toward an industrial indicator of productivity: doing lots of stuff in a visible manner.

This is why constantly answering emails and attending meetings can feel productive. It’s visible. Yet the truly productive work of an academic like Adam Grant, who isolates himself for days to write, looks like the opposite of busyness. I’ve seen this firsthand in countless organizations; the busiest people are often the least effective.

The second force is The Principle of Least Resistance. Without clear feedback on what’s truly valuable, we naturally default to behaviors that are easiest in the moment. Constant connectivity is easier than the hard planning and focus required for deep work, so we choose the path of least resistance, even when it sabotages our long-term effectiveness.

3. The Surprising Science Behind Elite-Level Deep Work

Achieving elite performance isn’t just about trying harder; it’s about fundamentally rewiring your brain. Two scientific concepts explain why deep work is so disproportionately effective.

How Deep Work Builds Brain Muscle

When you focus intensely on a specific skill, you’re forcing a particular neural circuit to fire repeatedly and in isolation. This repeated firing triggers cells to begin wrapping layers of a fatty tissue called myelin around the neurons in the circuits—effectively cementing the skill. Myelin acts as an insulator, allowing the neural circuit to fire faster and cleaner. To get good at something is to be well-myelinated.

This neurological process provides a clear explanation for why learning in a state of distraction is so ineffective. As the source material explains, “…if you’re trying to learn a complex new skill…in a state of low concentration…you’re firing too many circuits simultaneously and haphazardly to isolate the group of neurons you actually want to strengthen.” To learn hard things quickly is a physical act that requires the intense, isolated focus of deep work.

The Hidden Cost of a “Quick Check” of Your Inbox

According to research by professor Sophie Leroy, when you switch from one task to another, a residue of your attention remains stuck on the original task. She calls this phenomenon attention residue.

A quick glance at your inbox is devastating specifically because it introduces a high-residue switching cost. By seeing messages that you cannot deal with at the moment, you are forced to return to your primary task with a secondary, unfinished task now lodged in your mind. This creates significant attention residue that dampens your performance. As Leroy’s research concluded:

“People experiencing attention residue after switching tasks are likely to demonstrate poor performance on that next task.”

These scientific realities can be summarized with a simple formula for productivity: High-Quality Work Produced = (Time Spent) x (Intensity of Focus)

By working in a state of semi-distraction, you are sabotaging your intensity of focus and, therefore, the quality of your work.

4. To Master Deep Work, You Must First Embrace Boredom

The ability to concentrate is a skill. Like any other skill, it must be trained. This training will fail, however, if you spend the rest of your life fleeing the slightest hint of boredom.

Research from the late Stanford professor Clifford Nass revealed that constant multitasking and attention switching negatively rewires the brain. Heavy multitaskers are not just bad at multitasking; they’re bad at every aspect of focused thought.

“[Multitaskers have] developed habits of mind that make it impossible for them to be laser-focused. They’re suckers for irrelevancy. They just can’t keep on task.“

The solution is a radical shift in mindset: Don’t Take Breaks from Distraction. Instead Take Breaks from Focus.

A New Approach to Deep Work Training

Instead of occasionally unplugging from an otherwise connected life, try the opposite. Schedule in advance when you’ll use the Internet, and then avoid it completely outside those times. The goal is not to eliminate distraction, but to contain it.

This practice strengthens the “mental muscles” responsible for resisting distraction. Every time you feel the urge to switch your attention to something shiny and you resist, you’re completing a rep in your concentration workout. As Newport writes, this can be a surprisingly satisfying skill to cultivate. “I’m comfortable being bored,” he explains, “and this can be a surprisingly rewarding skill—especially on a lazy D.C. summer night listening to a Nationals game slowly unfold on the radio.” In a world where most can’t tolerate waiting in line for two minutes without pulling out a phone, this ability has become a novel but powerful asset.

Conclusion: Beyond Productivity

The economic necessity of deep work is clear, but our modern work culture, adrift in a metric black hole, actively works against it. The science of performance, however, reveals a way forward. By understanding that focus physically rewires our brains and that concentration is a skill that can be trained, we can fight back against the pull of the shallow.

But the pursuit of depth is about more than just economic rewards. A life defined by frantic, shallow pursuits is often a life of stress and unfulfillment. A life centered on deep work, on the other hand, is a life of meaning. The four truths of this article ultimately converge on a single, powerful conclusion from Newport:

A deep life is a good life, any way you look at it.

Cal Newport is a computer science professor at Georgetown University and a bestselling author known for books like Deep Work and Digital Minimalism. He writes for major publications and hosts the Deep Questions podcast, sharing advice on how to focus in a distracted world. Newport follows his own advice by completely avoiding social media and rarely working past 6 p.m., proving that deep concentration allows him to be highly productive in both his academic and writing careers.

Book details

- Title: Deep Work

- Explanatory Title: : Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

- Author: Cal Newport

- Publisher: MINDQUEST PRESS

- Publication Date: December 19, 2018

- Print Length: 304 pages

- ISBN-10: 1455586692

- ISBN-13: 978-1455586691

- Category: Personal Time Management / Time Management / Success Self-Help